Backgrounder: the “1033 program”

Speaking Security Newsletter | Congressional Candidate Advisory Note 16 | 9 June 2020

Some notes on the primary mechanism DOD uses to transfer military weapons and equipment to police forces.

1. The basics

The “1033 program” (from the section title in US law that authorizes the program) or “LESO program” (from the DOD office that runs the program, the Law Enforcement Support Office) has transferred more than $7.2 billion worth of DOD property to more than 8,000 US law enforcement agencies since its inception (FY1997) and transferred $293 million worth of military equipment in FY2019, $504 million in FY2017, and nearly $500 million in FY2011.

The program falls under the purview of DOD’s Defense Logistics Agency. It’s the largest agency inside DOD. DLA would qualify as a Fortune 50 company: it has 25,000 employees and is a ~$44 billion operation. Think of it like a federal, militarized WalMart that loses shit all the time. Oversight reports on DLA have reported mismanagement/gross incompetence since the 1990s. Auditors in early 2018 found DLA had misstatements worth at least $465 million and either didn’t have sufficient documentation or any at all for another $384 million worth of spending. Both pertain only to construction projects.

LESO has a similar track record. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has several reports on it, but the one that stands out to me is a 2017 report detailing how GAO created a fictional police department and obtained over 100 controlled items worth ~$1.2 million from the 1033/LESO program.

2. Origins/expansion

The Posse Comitatus Act of 1878 codified the separation of military and police into law. However, Congress has over time blurred the lines between warfighting and policing. One way is through authorizing the flow of military equipment to federal, state, and local police forces.

Congress first authorized DOD to start providing material support to state/local police in the context of the War on Drugs. 1988 legislation expanded DOD’s role in the interdiction of drug trafficking. In the early ‘90s Congress granted DOD temporary authority to transfer excess defense material, including small arms and ammunition from ‘excess’ DOD stocks, at no cost to the recipient police forces.

The 1997 NDAA made permanent DOD’s role and expanded the legal authority to include counterterrorism activities under Section 1033. The 2016 NDAA added “border security operations” to the list of preferences, alongside counterdrug and counterterrorism.

3. Process/priorities

*Basically: DOD has made sending its ‘excess’ equipment to state/local police a priority.

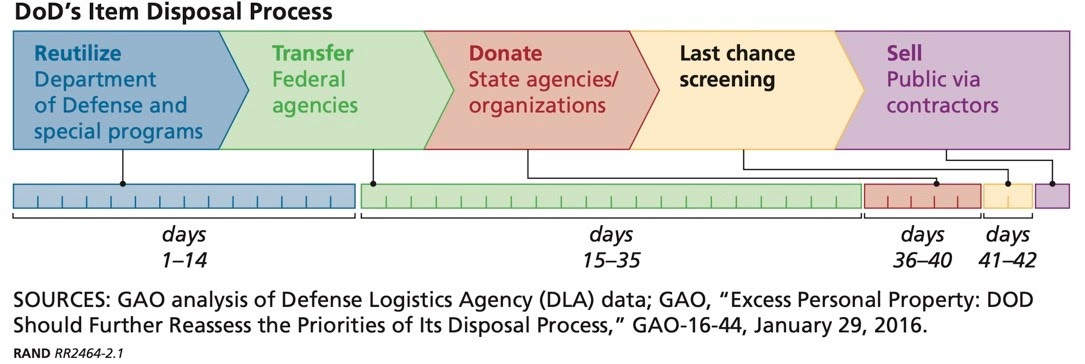

The process starts by DOD declaring that a piece of equipment is no longer necessary (‘excess’). Then the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) takes over. DLA advertises the thing on its website and tries to get rid of it through the process below.

Three things:

A. DLA disposes of 90 percent of ‘excess’ equipment within the first 14 days (in blue, above). This means that 90 percent of DLA’s stuff is either recycled back into DOD or is given away/sold through “special programs” (on a largely first come, first serve basis).

B. DOD gets preference over “special programs” but the latter is among the military services (Army, Navy, etc) as the first group eligible to request a piece of ‘excess’ military equipment posted by DLA.

C. The LESO/1033 program is classified as a “special program” (alongside Foreign Military Sales, which the US does a lot of).

4. Conclusion

Not going to reform our way out of this one. The militarism and incompetence runs too deep.

Before shutting the whole thing down, though, military-grade equipment should be taken back from the police:

In the previous note, I argued that if Congress was serious about demilitarizing police, members would order police forces to return “controlled” items (the problematic stuff) to the Department of Defense. Items in this “controlled” category legally remain DOD property regardless of how long the matériel has been in the hands of local law enforcement, anyway.

Hope this helps/thanks,

Stephen (stephen@securityreform.org; @stephensemler)